The erosion of universalism and the rise of identity politics

It's everywhere. But might the US have a chance to break out of it?

Several weeks ago I read a piece in the NZZ (Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the best German-language newspaper in the world and my local) that has been in my head ever since.

I will admit, it was the color photo of Amanda Gorman reciting her poem “The Hill We Climb” at the inauguration of US President Joe Biden in January 2021 that caught my eye.

In a flash all the feelings whirled through me. How beautifully honest and optimistic that reading was. The power of Amanda Gorman’s words. I was proud again, for a moment, of my birth country because this, THIS, was the society I grew up in. Her words are the lessons I have taken with me as I bounce through the world. The best parts of the US, the reasons why my great- and greater-grandparents moved there, the reasons why anyone goes there. The promise.

Watching that inaugural ceremony three and a half years ago, I started to think that Joe Biden might be more than just the safe pair of hands that would enable the US and the world to catch its breath a little and recalibrate.

Well. Now it is July 2024 and thinking about my visceral reaction to Amanda Gorman in January 2021 makes me feel very, very old indeed.

You + me = we? Not so much anymore

So I read the article. The German author and philosopher Leander Scholz1 wrote that the optimism expressed in Gorman’s poem was a very traditional American optimism of “we.” When I think back to the important lines we memorized in school, there was of course “We the people, in order to form a more perfect union”2 and this we was emphatically not a royal “we” but a most inclusive3 one. Amanda Gorman called upon this good old American “we” that pushes all our differences into the background when it comes to stepping forward into a new and better future.

Scholz opines that identity politics, this wave that has subsumed societies from the US to France to the UK to Russia to punching-above-its-weight Switzerland, fosters the radical opposite of “we.”

Identity politics does not create a sense of belonging. By its very nature, identity is defined by excluding others. Scholz argues that the movement of identity politics has given up on the encompassing “we” because that collective did not make good on all its epic promises.

Was it easier to maintain a unifying “we” during the bipolar Cold War? Leander Scholz thinks so. With the Iron Curtain dividing the world into two contrasting ideologies, there was not enough energy left over to nurture competing value systems within those two societies.

Attempts to create a new North-South division in place of the East-West blocs have resulted in these contrasting value systems rubbing elbows, according to Scholz. Post-colonialism considers universalism as an imposition of white, male values— hardly an integrative influence. What’s a multiethnic Europe to do?

In the multipolar world of the past 35 years, we’ve all been so busy defining our political selves by excluding the “other” that we’ve lost sight of just how many others there are. Instead of considering our common interests, we put up mental and physical walls to contain the “otherness.”

Is it really necessary to be breaking down societies into microscopic interest groups? Is universalism dead? I don’t think so. By defining ourselves according to what we are or where we have come from, we deny ourselves the possibility of defining a common future.

Meanwhile, across the water

In the days since US President Joe Biden decided to forego nomination for another term and instead endorsed his vice president, Kamala Harris, the first sighs of relief have turned into a euphoria of identity claiming. I read that a gathering of black women raised millions for Kamala within hours of the announcement. And in the socials, there are mini-electorates piping up to claim Kamala as one of their own.

I do hope that she is smart enough to graciously accept these accolades without over-identifying. Because if there is one thing that Kamala Harris should have learned these past four years in the orbit of an old school politician like Joe Biden, it is that she has arrived at a level of political vocation that goes far beyond remaining beholden to exclusionary groups. Kamala Harris is coming from a place of public service, for all Americans. That is a radically different positioning than “the half-Indian, half-black woman candidate from California” she was at the last election cycle.

One last hope that a President Harris could lead the US back to its principles of universalism? That “we” might again mean what Amanda Gorman intoned?

I am no longer a US citizen, so I can’t vote. And my son, still a US citizen, turns 18 two weeks after election day.4 However, there’s no use pretending that US politics has nothing more to do with me and my life, as much as I sometimes wish that were so. Aside from the immediate concerns for my family and friends, who have to live with the results, it still matters for the rest of the world. The US is still a great power— an occasionally limping, moody great power to be sure— and others measure their actions according to its reactions.

I want to live in a society that has titles like this. Or: What I wouldn’t give for that job title.

And now I am beginning to hum, thank you so much Schoolhouse Rock.

Okay, okay: if you were white, male and a landowner. But bear with me.

He was rather shocked when I told him if his birthday was in October, he’d be able to vote for the US President this year. Born and raised in Switzerland, he tends to forget about the blue passport, except when he travels to the US and has to dig it out. The idea of voting in future US presidential elections did not excite him much, either.

Good, turning 18 in Switzerland means entering into direct contact with the state, which occupies his mind more. He’s received his first call-up for military service and gets to vote here, which can be up to four times yearly on various and sundry. Poor child.

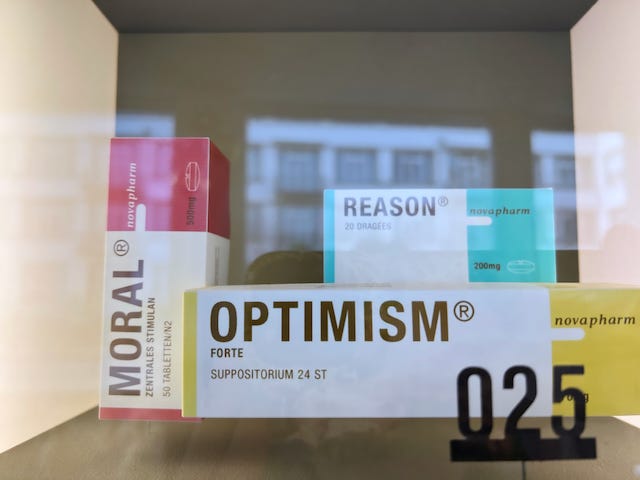

I think the “we” ran for several years after the end of the Cold War, and expanded in a much broader sense, beyond the US, to embrace old friends and relatives and newfound allies across the old East-West divide. That’s certainly how I remember the heady 1990s, although at the time I may have been high on Optimism and related endorphins. But it didn’t last long, and I suspect the rampant free-marketry and its inevitable subsequent inequalities may have had something to do with the demise of “we” and the emergence of identity politics. Another factor is the import by the North from the South of folk who adhere to an altogether different identity.